Do please allow me to introduce to you, Sophie’s World, by Jostein Gaarder (by the by, it was published in Norwegian in 1991 and then in English in 1994). It is a novel of sorts that seems to align with Bertrand Russell’s 1945, History of Western Philosophy. I say “of sorts” because essentially I see it as a way — one of many, see e.g.: “Put simply” — of making the key philosophers and their main ideas more accessible to the likes of me.

📙 Sophie’s World

inspired by Bertrand Russell’s:

📙 History of Western Philosophy

REFERENCE

Gaarder, J. (1994). Sophie’s World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

The novel centres on Sophie Amundsen, who is introduced to the history of philosophy by one Alberto Knox, a lecturer in philosophy by way of a number of letters and various other, often somewhat cryptic, mediums.

Every day, a letter comes to Sophie’s mailbox that contains a few questions and then later in the day a package comes with some typed pages describing the ideas of a philosopher who dealt with the issues raised by that morning’s questions. The philosopher, Alberto Knox, sends her these packages via his aptly named dog, ‘Hermes.’

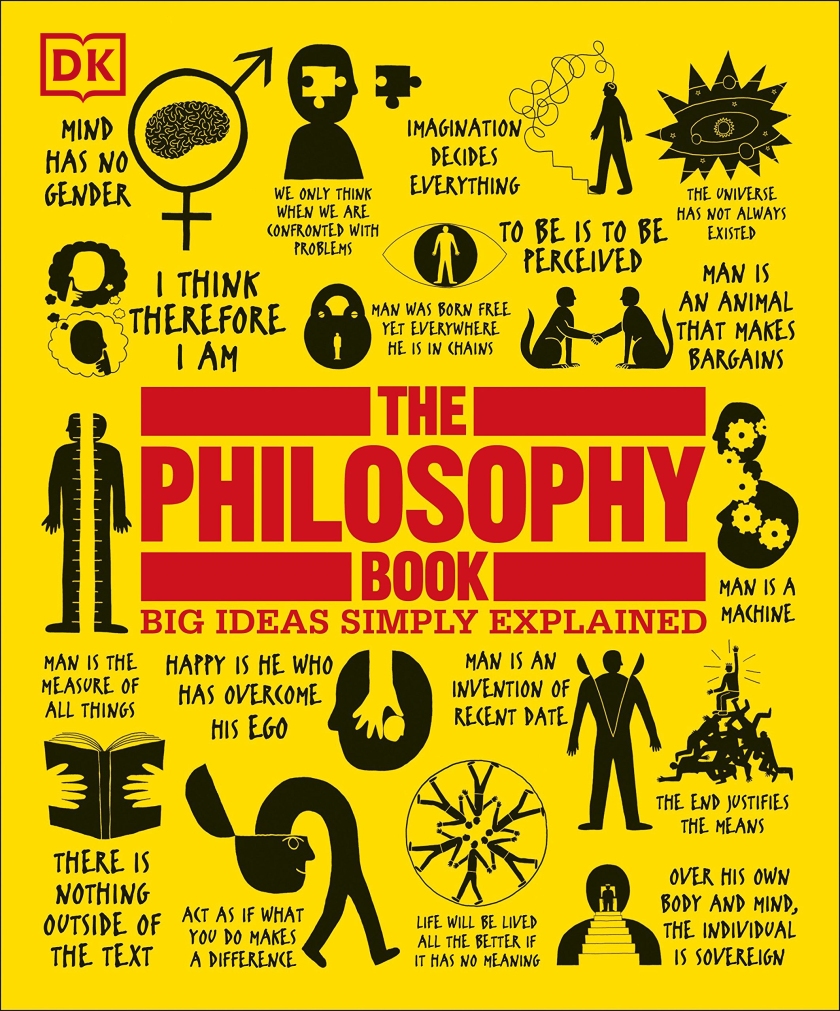

Alberto first tells Sophie that philosophy is extremely relevant to life and that if we do not question and ponder our very existence we are not really living. Then he proceeds to go through the history of Western philosophy. Sophie (and us readers) gets a reasonably coherent extended review from the Pre-Socratics to Jean-Paul Sartre. We get by way of Alberto, key points regarding the Renaissance, Romanticism, and Existentialism, as well as Darwinism and the ideas of Karl Marx. I thought it might be interesting to consider his categorisation, it is stated as being focused on ‘Western’ philosophy so the omission of the other canons is an acknowledged one.

Ancient Philosophy

— The Pre-Socratics

Including: Thales, Pythagoras, Heraclitus, Parmenides, Empedocles & Democritus

— Socrates, Plato & Aristotle

— Ancient Philosophy after Aristotle

Including: the Cynics, the Epicureans, the Stoics & Plotinus

Catholic Philosophy

— The Fathers

Including: St Augustine & Pope Gregory

— The Schoolmen

Including: St Thomas Aquinas

Modern Philosophy

— From the Renaissance to Hume

Including: Machiavelli, Erasmus, More, Bacon, Hobbes, Descartes, Spinoza, Locke & Hume

— From Rousseau to the Present Day

Including: Rousseau, Kant, Hegel, Byron, Nietzsche, the Utilitarians, Marx & William James.

I don’t like to paraphrase the following remarks but life ain’t always gunna b nice to you so, here goes, a reviewer at Publishers Weekly (familiarly known in the book world as PW and, they say, “the bible of the book business” has been printing out literary reviews since 1872 and somewhere along the timeline decided to drop the apostrophe) did write something along the lines of this: Regardless of age many readers will be tempted to skip over the somewhat “dryly written” philosophical lessons — which are not particularly integrated with the “more engaging” meta-fictional story line. This reminds me of something Li Yu is said to have said in his Carnal Prayer Mat.

❝

How low contemporary morals have sunk! But if you write a moral tract exhorting people to virtue, [you] will you get no one to buy it.

❞

Which is akin to the marketing adage/joke:

❝

SEX—

— Ah! Now that I have your attention, let me tell you about something completely different. . .

❞

Providing a polar opposite perspective is Steven Gambardella. He writes that Sophie’s World has changed the lives of millions of people and is the “red pill of literature.” It is “the best place to start reading about philosophy” and “eloquently captures the wonder of philosophy, the giddiness you feel when you realise you are floating in space.” The rabbit is sketched to be representative of the universe. In the book, we humans are compared to tiny insects in the rabbit’s fur. Some of us burrow down into the warmth of the fur, while the philosophers among us climb to the tops of the hairs “to stare right into the magician’s eyes.” As Gambardella states, it was written by a high school teacher with a passion for the subject, became a bestseller and has now “sold over 40 million copies.”

![Going [reaching || falling] down the rabbit hole](https://bidoonism.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/rabbit-hole-also.jpg?w=840)

By Salvador Dalí (1931). One of the most recognisable works of Surrealism [Spanish title: La persistencia de la memoria].

❝

Without [Philosophical pondering] no one can lead a life free of fear or worry. Every hour of the day countless situations arise that call for advice, and for that advice we have to look to [it].

❞

Me, well I’m a dipper (skinny I wish) and this applies to all that I read and my writings and musings too. The chalice or urn is neither overflowing or bone dry. It is, I submit to you, bang in the middle. The purpose of this book in my view is to encourage us to think for ourselves, question things that are taken as given and doubt dogmas, as Gaarder writes, “my concern [, dear Sophie,] is that you do not grow up to be one of those people who take the world for granted.” I’d take the red over the blue, politically and metaphorically speaking and in relation to the pleasures and pains of love too.

I’ll end with a nod to who I’m guessing was an influence on Gaarder: Bertrand Russell. Russell was an English philosopher and campaigner for freedom (of expression and from authoritarian control). Reassuringly — to me anyway — he said do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once seen as being eccentric.

❝

Of all forms of caution, caution in love is perhaps the most fatal to true happiness.

❞

— Bertrand Russell

❝

The fundamental cause of trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.

❞

— Bertrand Russell

p.s.

Consider visiting Bidoonism’s page on Philosophy and/or reading her recent reviews of the following works:

Eldridge, R. T. (Ed.). (2009). The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gottlieb, A. (2000). The Dream of Reason: a History of Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Gottlieb, A. (2016). The Dream of Enlightenment: The Rise of Modern Philosophy. London: Penguin.

Grayling, A. C. (2019). The History of Philosophy. London: Penguin.

Kenny, A. (1998). An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy. New York: John Wiley & Sons

Russell, B. (1945). A History of Western Philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.