A literary analysis of Susan Stewart’s “A Language.”

“A Language”

❝

I had heard the story before

about the two prisoners, alone

in the same cell, and one

gives the other lessons in a language.

Day after day, the pupil studies hard—

what else does he have to do?—and year

after year they practice,

waiting for the hour of release.

They tackle the nouns, the cases, and genders,

the rules for imperatives and conjugations,

but near the end of his sentence, the teacher

suddenly dies and only the pupil

goes back through the gate and into the open

world. He travels to the country of his new

language, fluent, and full of hope.

Yet when he arrives he finds

that the language he speaks is not

the language that is spoken. He has learned

a language one other person knew—its inventor,

his cell-mate and teacher.

And then the other

evening, I heard the story again.

This time the teacher was Gombrowicz, the pupil

was his wife. She had dreamed of learning

Polish and, hour after hour, for years

on end, Gombrowicz had been willing to teach

her a Polish that does not and never

did exist. The man who told

the story would like to marry his girlfriend.

They love to read in bed and between

them speak three languages.

They laughed—at the wife, at Gombrowicz, it wasn’t

clear, and I wasn’t sure that they

themselves knew what was funny.

I wondered why the man had told

the story, and thought of the tricks

enclosure can play. A nod, or silence,

another nod, consent—or not, as a cloud

drifts beyond the scene and the two

stand pointing in different directions

at the very same empty sky.

Even so, there was something

else about the story, like teaching

a stunt to an animal—a four-legged

creature might prance on two legs

or a two-legged creature might

fall onto four.

I remembered,

then, the miscarriage, and before that

the months of waiting: like baskets filled

with bright shapes, the imagination

run wild. And then what arrived:

the event that was nothing, a mistaken idea,

a scrap of charred cloth, the enormous

present folding over the future,

like a wave overtaking

a grain of sand.

There was a myth

I once knew about twins who spoke

a private language, though one

spoke only the truth and the other

only lies. The savior gets mixed

up with the traitor, but the traitor

stays as true to himself as a god.

All night the rain falls here, falls there,

and the creatures dream, or drown, in the lair.

❞

— Susan Stewart

Before I consider the above poem, which I do deeply like, I just must point to the following words by Stewart — they were penned for an academic text, 📙 The Handbook of Philosophy, demonstrating her versatility as a wordsmith (oh how I wanna b 1 2)… :

Philosophy, the love of wisdom, and lyric, words meant to be sung to the musical accompaniment of a lyre, seem, at least etymologically, to have little to do with each other. Philosophers may even say we make a category mistake in comparing them, since the first term refers to the pursuit of knowledge of truth and the second term refers to an expressive art form. Yet both philosophers and lyric poets are solo speakers, and their common material is language—indeed, they share the same language, for it is not that there are separate tongues for each. Philosophers and poets are alike in certain actions, as well: they convey intelligible statements; employ formal structures with beginnings, middles, and ends; and hope to convince or move their audiences, and so incorporate a social view from the outset.

. . .

Nevertheless, … the language of philosophy strives for clarity and singularity of reference. Lyric, in contrast, is always over-determined; its images, symbols, sounds, the very grain of the voices it suggests, all compete for our attention and throw us back, whether we are listening or reading, to repeated consideration of the whole. Philosophy should be paraphrasable and translatable if its truth claims are universal, but poetry has finality of form, and to paraphrase it is a heresy; to translate it, a betrayal.

By the way, it was while reading her chapter in 📙 The Handbook of Philosophy on the lyric genre that I wondered who exactly Susan Stewart was. I investigated (one thing led to another) and found the poem cited above and considered below (and my plans for reviewing the text that my schedule say I should have gone absent without a leg to stand on).

As he’d say to me, “dig deeper, keep on digging”

↘

Oh for Ireland / Joyous for Heaney.

The poem

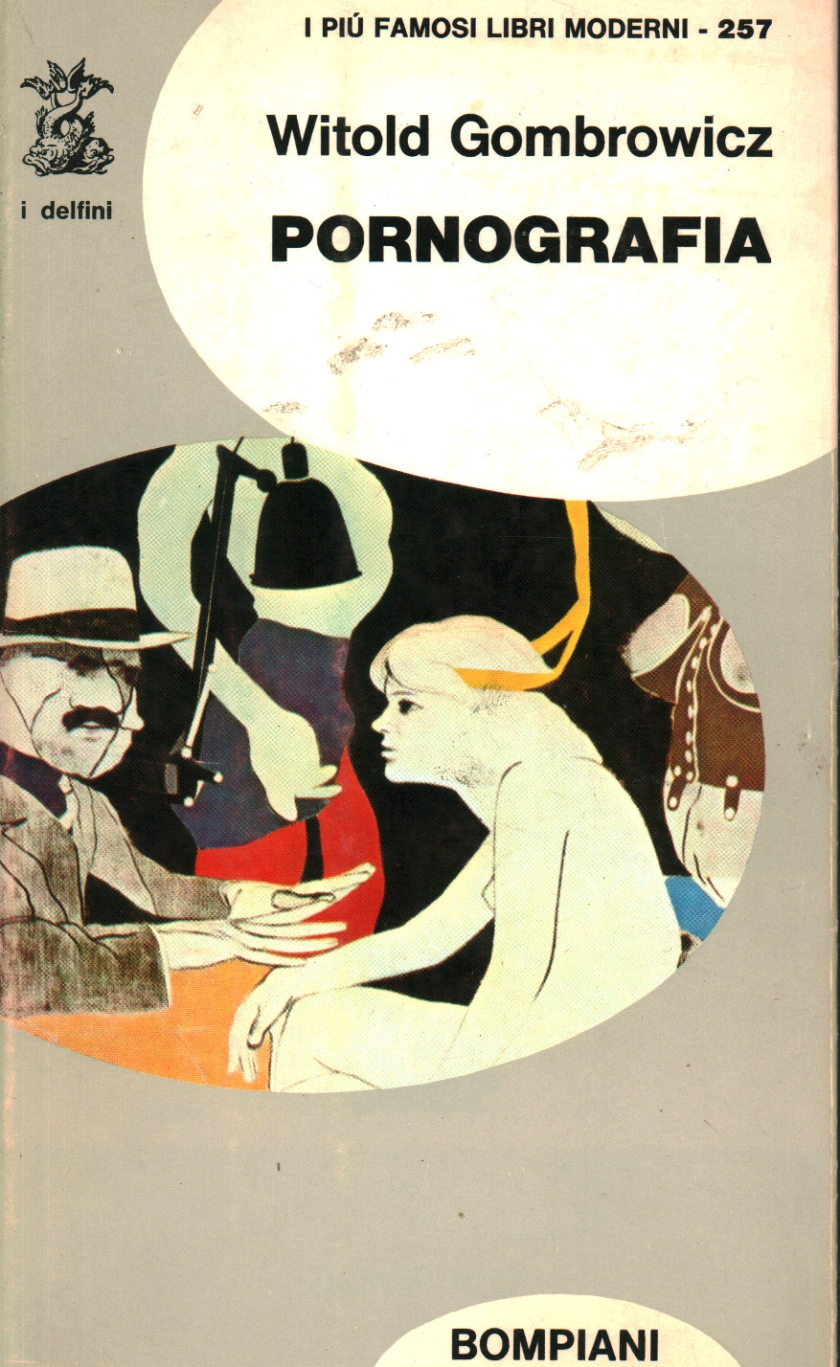

I’ll comment on the six parts of “A Language” here (six as I see them). But, in short, the poem seems to be about dream vs. reality, about deceit (intentional or otherwise, by one’s self to one’s self or by one to another) about contradiction, and about love (lost, misplaced and blind). It was amusing me until the miscarriage — it read too much like being real, i.e., drawn from the author’s very own life experience. The last two lines ain’t italic and that’s the author’s switch of emphasis, not mine. Witold Gombrowicz — a Polish writer (1904–1969) with an interesting bio (as anti-establishment, anti-religious bisexual kind of guy, his books were banned in communist Poland) — said with regard to literary criticism, and I do quoteth the man: “Literary criticism is not the judging of one [soul] by another therefore, do not judge. Simply describe your reactions. Never write about the author or the work, only about yourself in confrontation with the work or the author. You are allowed to write about yourself.” *

Part one

To begin at the beginning I felt it would link to the prisoner’s dilemma but it didn’t.** It was about trickery, but the language may well have been code for the language of love. The intimacy built with one other cannot – ctrl C, ctrl V – be just transferred from the one to an(y )other one. Maybe the deceit lay in the older more learned one not teaching adequately the singularity of true love, it, like Halley’s comet, is a once in a lifetime thing.

I had heard the story before / ...

I had heard the story before.

I didn’t read in between the lines that the student felt annoyance for his/her post-prison discovery.

Part two

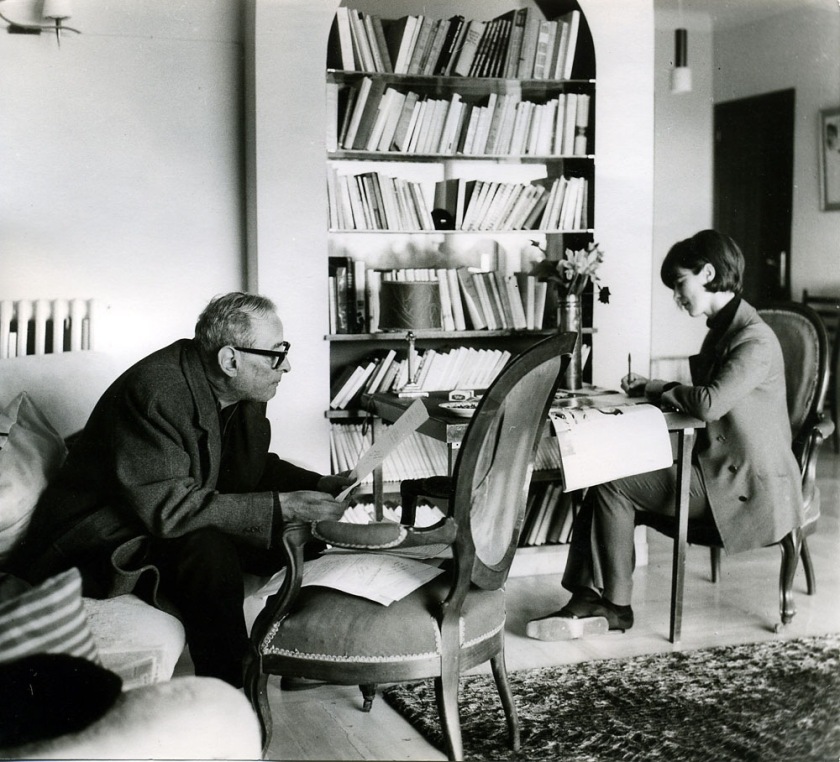

Underscoring Part 1, but here making reference to a real world relationship, that of the writer Gombrowicz and his (much younger) muse.

And then the other evening, I heard the story again / ...

the tricks enclosure can play / ...

at the very same empty sky.

We might be together, but we may be worlds apart too. Tricks reads a little comparatively, is this the poem’s narrator recalling the honeymoon period of a former or a current relationship. undergraduates bedding down with books and the positivity bestowed from having a lifetime of dreams and plans to look forward to.

Part three

Even so, / ...

... fall onto four.

We can learn to do various things, things that have no real utility, point or purpose whatsoever.

Part four

Very powerful and the mood of the poem abruptly changes (for me anyway).

I remembered, then, the miscarriage / ...

the enormous present folding over the future, /

like a wave overtaking a grain of sand.

I feel this to be all too real.

Part five

Such stories of twin as co-collaborators are commonplace. The word “myth” speaks volumes here. Did the miscarriage herald the end of the narrator’s once perfect relationship? The myth of forever love… And then in comes a god and ‘his’ arch-nemesis the dastardly devil.

There was a myth I once knew / ...

the traitor stays as true to himself as a god.

Good and Evil, this is great! Stewart here becomes a philosopher and made me realise something that should have been obvious. (Oh Life / Woman Alive / Wax Lyrical.) The devil doesn’t falter and stays true to his typecast pigeon hole. Yet the given god transcends from savior to traitor.

↘

I’m choosing my confessions /

Like a hurt lost and blinded fool.

Part six

The ending (two lines, a different mode of typed-text emphasis) is short and is sans-sanguinity. We are creatures just the same as the birds and the bees; the sacrificial lambs, the holy cows and the bunnies busily beavering away.

All night the rain falls here, falls there, /

and the creatures dream, or drown, in the lair.

The rain falls on us all, rich or poor, happy or sad, female or male. We either live the dream in our dream or we sleepwalk into the labyrinthine maze that is our torment of torrential thoughts on what might have been, what could’ve been for: what once was, no longer is.

All in all, there’s sadness here isn’t there — the empty sky, the dark rainy night — where, if you don’t fantasise and delude yourself, you’ll drown in black-mood depression. Everything you’d planned for — taken as faith, taken at face-value, taken for granted; taken as a given — is abruptly and inexplicably taken away from you. Be it faith in fellow man, faith in your muse, faith in what you’d believed to have been your partner for life; the prospect of a soon to be born insatiably innocent (genes aside) version of yourself.

— § § § —

— § § § —

Foot fetish notes

* The prisoner’s dilemma is a paradox in decision analysis (a.k.a., ‘game theory) in which two individuals acting in their own self-interests do not produce the optimal outcome. In other words, if both were to be altruistic toward the other they’d both do well. My sophisticated ethics teacher told sought to explain this to us by way of the medium of money. She said: you could both take 50 Riyal now or if you both forfeit the Riyal now (the honey tomorrow thesis) you’ll both get 100 Riyal tomorrow, but if any one of you takes the 50 now and the other doesn’t the one who takes the money gets to have their small amount of honey today whereas the other will get nothing. So, (1) knowing that most humans are considered to be selfish and also (2) not being able to communicate with the other prisoner, she said that (3) most would grab the 50 because few would risk foregoing it for the possibility of 100. The natural assumption is that the other prisoner would be short-termist in character and go for the guarantee of a few Riyals today as opposed to the prospect of far more Riyals tomorrow.

** As a critic in The New Yorker said in 2012, his “grotesque, erotic, and often hilarious stories” soon established Gombrowicz as a widely read author. His fiction’s been deemed as creepy as Poe’s and as abusurdist as Kafka’s. ((A man encounters another man by chance at the opera and shadows him for weeks—sending him flowers, writing letters to his mistress—unaware of the torment his attentions are causing.)) ((A countess famous for her meatless dinners may, it turns out, be serving human flesh.)) Gombrowicz himself said of his writing that he was, “never more satisfied than when my pen gave birth to some scene that was truly crazy, removed from the (healthy) expectations of mediocre logic and yet firmly rooted in its own separate logic.”

I’ve always found it so hard to these poetic analysis; either for school or in general. I’m not good at stratifying knowledge and interpretation. I have a muddled brain. You’re marvelous at it, though.

I think the miscarriage point was (and I might be absurdly wrong here) a purposeful shift in tone to destabilise the precise nature of absorption herein (the poem); you get thrown into a whirl of the sensorial and imaginary, your dream/reality, as you put it, but that emotional bluntness, that sharp puncture to the pith functions like a dark heart in the poem. It tethers it.

I use that device sometimes, in my poems, whenever they lend themselves to its usage. Katabasis, for instance, was about a father figure that raised me from very young, and he died when I was about 10. I know, now, how disappointed he’d be, were he alive. Hence the repeated line in the poem: “Your misfortune has so many patterns.”

I maunder; you’re awesome, Anna.

LikeLiked by 1 person

κατάβασις

————

I’ll begin my reply by thanking you sincerely for your attention and time. I am fascinated by your insights regarding poetic shifts and moved to investigate (and reread) “Katabasis”—intrigued, to say the least, by the certainty with which you feel he’d be disappointed, were he to be alive today. Buoyed by the coloured stepping stones in those stanzas, I’ll scud buoyantly along aided by this summer’s simoom (yet abetted by Hans Wehr) and undertake to dig down further.

————

Whilst we most of us inevitably descend, the door up to paradiso will invariably be left ajar.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, Anna, it’s no insight at all. I speak from experience, but I have little of that.

The composition is not particularly good; well, none of mine are, but I find that Katabasis is overly emotional, even for me. It’s too spastic and lugubrious, which, I suppose, were the sentiments that informed it.

And an anabasis always follows a katabasis; one might not reach paradiso, but one leaves hell, and that is lofty and paradisaical for many. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person